Josh Keyes' style is reminiscent of the diagrammatic vocabulary found in scientific textbook illustrations that often express through a detached and clinical viewpoint an empirical representation of the natural world. Assembled into this virtual stage set are references to contemporary events along with images and themes from his personal mythology. Josh Keyes' work is a hybrid of eco-surrealism and dystopian folktales that express a concern for our time and the Earth's future.

Josh Keyes was born in Tacoma, Washington. He received a BFA in 1992 from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA in 1998 from Yale University. Keyescurrently lives and works in Portland Oregon.

New Art Works

"100 years of art till Now."

Monday, March 26, 2012

Marina Abramovic

Childhood

Marina Abramovic was born in 1946 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia to parents who held prominent positions in the Communist government. Her father, Vojin, was in the Marshal's elite guard and her mother, Danica, was an art historian who oversaw historic monuments. After her father left the family, her mother took strict control of eighteen-year-old Abramovic and her younger brother, Velimir. Her mother was difficult and sometimes violent, yet she supported her daughter's interest in art. While growing up, Abramovic saw numerous Biennales in Venice, exposing her to artists outside of Communist Yugoslavia such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Louise Nevelson.

Early training

Abramovic studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade (1965-1970), and at Radionica Krsta Hegedusic, Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (1970-1972). It was in the early 1970s that she began creating performative art, initially creating sound installations, but quickly moving towards works that more directly involved the body. During this period she taught at the Academy of Arts, University of Novi Sad (1973-1975).

Mature period

In her early work, Abramovic often placed her body in danger: she took drugs intended to treat catatonia and schizophrenia (Rhythm 2, 1974); she invited viewers to threaten her body with a variety of objects including a loaded gun (Rhythm 0, 1974); and she cut her stomach with a razor blade, whipped herself, and lay on a block of ice (Thomas Lips, 1975). She has suggested that the inspiration for such work came from both her experience of growing up under Tito's Communist dictatorship, and of her relationship with her mother: "All my work in Yugoslavia was very much about rebellion, not against just the family structure but the social structure and the structure of the art system there... My whole energy came from trying to overcome these kinds of limits." Accordingly, these rebellious performances, which took place in small studios, student centers and alternative spaces in Yugoslavia, ended by 10pm, the strict curfew set by her mother.

Abramovic created these pioneering works when performance art was still a new, emerging art form in Europe, and until the mid 1970s she had little knowledge of performances being done outside Yugoslavia - even then, she learned of such work only through word of mouth. But in 1975, while in Amsterdam, Abramovic met the German-born artist Frank Uwe Laysiepen - known as Ulay - and the next year she moved out of her parents' home for the first time to live with him. For the next 12 years, Abramovic and Ulay were artistic collaborators and lovers. They traveled across Europe in a van, lived with Australian Aborigines, and in India's Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, and spent time in the Sahara, Thar and Gobi deserts. Their works, which they performed in gallery spaces primarily in Europe, included Imponderabilia (1977), in which they stood naked in a narrow doorway, forcing spectators to pass between them; Breathing In/Breathing Out (1977), in which they inhaled and exhaled from each other's mouths until they almost suffocated; Relation in Time (1977), involving them sitting back to back with their hair tied together; Light/Dark (1977), in which they alternately slapped each other's faces; and Nightsea Crossing (1981-1987), a performance in which the pair sat silently opposite each other at a wooden table for as long as possible. When Abramovic and Ulay decided to end their artistic collaboration and personal relationship in 1988, they embarked on a piece called The Lovers; each started at a different end of the Great Wall of China and walked for three months until they met in the middle and said goodbye. They have had very little contact with each other since that point, both proceeding independently with their artistic work.

Late period

After this separation from Ulay, Abramovic returned to making solo works; she also worked with new collaborators such as Charles Atlas (on Biography, 1992); and she worked increasingly with video (such as in Cleaning the Mirror #1, 1995). In 1989, she began making a number of sculptural works, Transitory Objects for Human and Non-Human Use, which comprise objects meant to incite audience participation and interaction. In addition to her performances during the 1990s, Abramovic taught at the Hochschule der Kunste in Berlin and the Academie des Beaux-Arts in Paris (1990-1991), as well as the Hochschule fur Bildende Kunste in Hamburg (1992). Beginning in 1994 she taught for seven years as a performance art professor at the Hochschule fur Bildende Kunste in Braunschweig, Germany.

She was awarded the Golden Lion for Best Artist at the Venice Biennale for Balkan Baroque (1997), and in 2003 she won a New York Dance and Performance Award ("Bessie") for The House with the Ocean View (2002), performed at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. In 2005, she restaged performances by artists such as Vito Acconci and Bruce Nauman, as well as her own Thomas Lips (1975) in an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum called "Seven Easy Pieces", for which she earned a U.S. Art Critics Association Award.

While many artists, including Abramovic, made very little effort in the early 1970s to capture their performances on film or video, feeling that the true performance could never be repeated, she has since argued for the importance of continuing the life of these works through re-performance. She has said, "the only real way to document a performance art piece is to re-perform the piece itself." To that end, the Museum of Modern Art recently held a retrospective exhibition - its first ever for any performance artist - that included performances of her work and a new piece, The Artist is Present, performed by Abramovic herself. For the full duration of the 2010 exhibit, she would sit across from an empty chair in which museum visitors were invited to sit opposite her for as long as they liked.

LEGACY

Abramovic, who has referred to herself as, "the grandmother of performance art," was part of the earliest experiments in performance art, and she is one of the few pioneers of that generation still creating new work. She has been, and continues to be, an essential influence for performance artists making work over the last several decades, especially for works that challenge the limits of the body. Although she does not view her own artwork through the frame of Feminist Art, her confrontations with the physical self and the primary role given to the female body have helped shape the direction of that discipline. Her commitment to giving new life to older performance works - both hers and the works of others -- led her to create the Marina Abramovic Institute for Preservation of Performance Art, set for a 2012 opening, in Hudson, New York. This non-profit organization will support teaching, preserving and funding performance art, ensuring an enduring legacy for her performances and, more broadly, for the ephemeral art form itself. About this Institute, Abramovic has said, "Performance is fleeting. But this, this place, this is for time. This is what I will leave behind."

For more information: http://www.theartstory.org/artist-abramovic-marina.htm

Friday, March 23, 2012

Wangechi Mutu

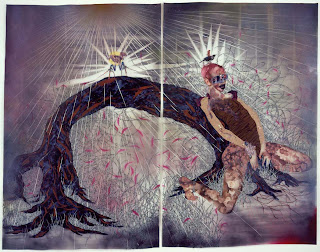

Kenyan-born Wangechi Mutu has trained as both a sculptor and anthropologist. Her work explores the contradictions of female and cultural identity and makes reference to colonial history, contemporary African politics and the international fashion industry. Drawing from the aesthetics of traditional crafts, science fiction and funkadelia, Mutu’s works document the contemporary myth making of endangered cultural heritage.

Piecing together magazine imagery with painted surfaces and found materials, Mutu’s elaborate collages mimic amputation, transplant operations and bionic prosthetics. Her figures become satirical mutilations. Their forms are grotesquely marred through perverse modification, echoing the atrocities of war or self-inflicted improvements of plastic surgery. Mutu examines how ideology is very much tied to corporeal form. She cites a European preference to physique that has been inflicted on and adapted by Africans, resulting in both social hierarchy and genocide.

Mutu’s figures are equally repulsive and attractive. From corruption and violence, Mutu creates a glamorous beauty. Her figures are empowered by their survivalist adaptation to atrocity, immunized and ‘improved’ by horror and victimization. Their exaggerated features are appropriated from lifestyle magazines and constructed from festive materials such as fairy dust and fun fur. Mutu uses materials that refer to African identity and political strife: dazzling black glitter symbolizes western desire that simultaneously alludes to the illegal diamond trade and its terrible consequences. Her work embodies a notion of identity crisis, where origin and ownership of cultural signifiers becomes an unsettling and dubious terrain.

Mutu’s collages seem both ancient and futuristic. Her figures aspire to a super-race, by-products of an imposed evolution. In this series of work, she uses old medical diagrams, to convey the authenticity of artifact, as well as an appointed cultural value. Satirically identifying her ‘diseases’ as a sub/post-human monsters, she invents an equally primitive and prophetically alien species; a visionary futurism inclusive of cultural difference and self-determination.

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Damien Hirst

Damien Hirst was born in Bristol in 1965. He grew up in Leeds with his mother, Mary Brennan, and his stepfather. He took a foundation course at Leeds School of Art before applying for college. He was rejected by St. Martin's but moved to London in 1986 when he was accepted onto the BA Fine Art course at Goldsmiths College, graduating in 1989. While still a student in 1988, Damien conceived, organised and promoted "Freeze", an exhibition held in a Docklands warehouse. The show featured several of Damien's pieces, and work by 16 of his fellow Goldsmith's' students.

This amazingly successful self-promoted exhibition is widely believed to have been the starting point for the "Young British Artists" movement. After seeing Damien's work at the show, Charles Saatchi (ex Thatcher ad-man), began to collect his work and exhibited it in the first "Charles Saatchi's Young British Artists" show. In 1990, Saatchi bought Damien's A Thousand Years. Since then, he has produced a body of work that, admired from the start by collectors and curators, has also proved extraordinarily provocative. In 1992, he commissioned the piece The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living for about US$32,000. He has organised a succession of exhibitions that have helped to define a generation.

Damien's generation is one completely different from previous generations of artist. The Young British Artists are characterised by their independence, their entrepreneurial spirit, and their media savvy. Most promote their own shows, and are financed privately instead of by the Department of National Heritage establishment. This way, they needn't worry about being "discovered" by the conservative governmental agencies, and instead tend to draw in private patrons, like Saatchi.

The central, though not exclusive theme of Hirst's work has been an exploration of mortality, a traditional subject that Hirst has updated and extended with wit, verve, originality and force. He is best known for a series of works (The Natural History series) in which dead animals are presented as memento mori in forms ironically appropriated from the museum of natural history rather than of art. Their titles suggest a range of readings and reveal the thoughtfulness of his approach. The artwork itself has a visual power that is virtually unmatched by any possible description of it. One cannot really hope to understand it, or even visualise it without experiencing it firsthand. This, many people believe, is the reason Damien was short listed for the Turner Prize in 1992.

Even his own supporters do not always acclaim his work. The popularity of Hirst's unique brand of artistic statement tends to cycle in phases of favour and disdain. In April 1993, Hirst's God sold at the highest price of any of his pieces to date: 188,500 pounds. In October 1993, however, his exhibit Alone Yet Together, which consisted of a cabinet holding 100 fish suspended in small tanks of formaldehyde, was set to auction for nearly 150,000 pounds. The bidding closed at only 85,000, and failed to sell. His piece entitled Loss of Memory is Worse Than Death (a steel cage encasing several vitrines which contained a surgical mask, gloves, and a syringe) also failed to sell, closing at 55,000 pounds (less than half of the maximum expected bid).

Damien blames this occasional lack of success not on the public, but on the press. He says that the media convinces the public to believe the art critics' erroneous assumptions about art, so the public accepts these opinions without ever actually viewing the art. In this manner, the public is alienated from an art world that they could find very enjoyable if they gave it a fair chance. Many people who agree with this idea also believe that the art critics themselves are influenced in their opinions by the media. They go in to review a work of art with a preconceived opinion, and do not allow the art to affect them the way it should. By distancing themselves from the art, they are cheating themselves of the full experience.

Some members of the media argue this point, saying that the art is not accessible to the public, that they cannot understand it without an art degree. Damien argues that the public has the ability to understand and appreciate art because of their extensive visual background knowledge. People view complicated visual structures in advertising and understand it, and art is merely another form of those visual structures. He claims that if people were to attend art shows as frequently as they see films and advertisements, they would understand the art. He believes, "the same visual intelligence and visual language are used to understand films, advertising, and art".

Even so, Damien constantly has to explain his work. Besides the controversial animal exhibits, there are sculptures, spot paintings and spin paintings. Damien now insists that when the spin paintings are displayed, they are equipped with a mechanism that makes them revolve on the wall because he was tired of people asking which way was up. The spot paintings have become somewhat of an icon of Damien's work. They have become so recognisable as Damien's theme that he actually brought suit against British Airways in 1999 for an advertisement campaign for their low-cost airline, Go, which used the motif. In that same year, Damien was asked to create a special spot painting to send into space for the Beagle II mission to Mars in 2003.

There are also many recurring themes in Damien's work. One such theme is cigarettes - see his piece Party Time as an example. He views the act of smoking as a microcosm within itself: "The cigarette packet is possible lives, the cigarette it's own actual life, the lighter is God because it gives fuel to the whole thing and the ashtray is a graveyard, it's like death". Damien is also fascinated by the fact that smoking is a "theoretical suicide" in the sense that it is not deliberate self-inflicted death, but people know it will kill them and they continue to partake. He stated that "the concept of a slow suicide through smoking is a really great idea, a powerful thing to do".

Another consistent theme in Damien's work is medical paraphernalia, (with which he has been obsessed for many years). The inspiration for his pharmacy pieces was the desire to make art that people really believe in, like they do medicine. "Pharmacies provoke an idea of confidence, of trust in minimalism. I love medical logos, so minimal, so clean, there's something dumb about it". His pieces like Substitute, Holidays/No Feelings and God are meant to parody the Western notion that medicine and chemicals can help a person to cheat death. "You can only cure people for so long and then they're going to die anyway... You can't arrest decay, but these works suggest you can".

Damien's works relating to empty, confined spaces "draw their power entirely from the narrative instincts of the viewer". One sees a tiny cage-like enclosure, confined by glass, with a desk, chair, and other objects that are normally meant for human interaction (see He Tried to Internalise Everything and The Acquired Inability to Escape). And then one notices the emptiness - the lack of human presence in this familiar scene. "It is almost impossible to avoid mentally inhabiting it. This transforms the viewer's function from that of an exploratory intelligence, to that of a rather doubtful collaborator (or victim). This is work which asks to be experienced, not solved." The fact that they are encased in glass allows the viewer to interact with the art, but it is a frustrating interaction. "The intellect is still engaged, but it is an intellect involved in an anxious body, viscerally conscious."

Damien says, "I really love glass, a substance which is very solid, is dangerous, but transparent. That idea of being able to see everything but not able to touch, solid but invisible. The slits in the glass are very important to the works, you need some sort of access". In pieces where the glass structures enclose, say, a rotting animal carcass (A Thousand Years), that access can be a bit much for some viewers, as the smell is sometimes overpowering, but it is a major part of the experience of the works. The smell draws the viewer in undeniably, they experience the piece and are not allowed to distinguish themselves as mere observers. This is part of what makes many of Damien's works so engaging and frightening.

Many of Damien's animal works are unlike A Thousand Years in that they are not supposed to go through any more natural processes. In fact, he goes through an immense amount of trouble to completely preserve them in formaldehyde. Many have questioned Damien about whether he is bothered by the possibility that corpses will eventually rot anyway. He replies that he is not concerned because he claims that the idea is more important than the actual piece. As long as they last until the end of his own lifetime, he doesn't care what happens to them after.

Damien's "Natural History" series, the works involving the animals preserved in formaldehyde, are probably his most famous, and definitely his most controversial. But his own attitude towards the animals is emotionally distant. They are "so deadened by their transparent aqua tombs that it becomes difficult to reconcile what they look like with the reality of what they really are. In this respect, they are as distant from cows or pigs as the filling of a Big Mac or BLT". One such example is Mother and Child, Divided, a piece from his exhibition "Some Went Mad, Some Ran Away" for which he was awarded the Turner Prize in 1995. Damien says, "I want to make people feel like burgers. I chose a cow because it was banal. It's just nothing. It doesn't mean anything. What is the difference between a cow and a burger? Not a lot... I want people to look at cows and feel 'Oh my god', so then in turn, it makes them feel like burgers."

His emotional distance from the animals also allows him to make his work sometimes sickeningly funny. In This Little Piggy Went to Market, This Little Piggy Stayed Home, each half of a bisected pig in tanks of formaldehyde, slide past one another on an automated track, separating and putting themselves back to together over and over again. He says, "I hope that it makes people think about things that they take for granted. Like smoking, like sex, like love, like life, like advertising, like death... I want to make people frightened of what they know. I want to make them question." He achieves this by incorporating common objects into his work. "Ordinary things are frightening. It's like, a shoe is intended to get you from one place to another. The moment you beat your girlfriend's head in with it, it becomes something insane. The change of function is what's frightening... That's what art is."

Not everyone, though, is so emotionally distant from the animals in Damien's art. Many people either can't stomach it, or have some moral objection to it. Damien has received many letters of protest, and even some threats. While the negative reaction to his work is perhaps understandable, it is not necessarily warranted, as the animals he uses are purchased from slaughterhouses, and many have died of natural causes. Damien himself is actually sympathetic to the animals, taking something purely banal, and pointing out the reality of its existence. "I hope [the viewers] feel sorry for the cows".

However, it's not just the objectors who cause problems for Damien. In 1994, he had an extreme amount of trouble getting his art into the United States to exhibit it. The first piece was delayed at US Customs until it was established that the animals were considered art and not food. Then a piece that was to be displayed in New York City was banned by the Health Department because they were concerned about the "odors and fluids created by the rotting process". And finally, the US Department of Agriculture banned a piece from another New York show because of the temporary ban on British beef. Damien explained: "They were worried that if someone ate it, there was no evidence that the formaldehyde would kill BSE (mad cow disease). I told them that nobody's going to eat it but they said that's not the point. I told them that if anyone ate it, the formaldehyde would kill them anyway, but they said that's not the point either". After two days, Damien convinced them that this piece was also to be considered art, and not food.

In August of 1995, another New York gallery banned Damien's Two Fucking, Two Watching, which involves a dead cow and bull copulating by means of a hydraulic device. The piece was not preserved in formaldehyde, but rather was left to rot away. New York health officials were concerned that it might "explode" (if it were sealed shut, the methane gasses would build up and shatter the glass), or "prompt vomiting among the visitors" (if it were not sealed shut, as the odor from the rotting carcasses would be "overwhelming"). So Damien brought in a new piece, which was preserved and would have none of these problems. "The new cow piece replaces the one I really wanted to do, the dead cows fucking, without formaldehyde. We called up the environmental department and told them what we'd have: rotting animals, but with filters to clean the air. They said 'if you do that we'll shut you down'".

He faced a vaguely similar situation in 1999 when there was a mass of controversy over the "Sensation" exhibition when it arrived in Brooklyn, New York. Though there was a small bit of protest over Damien's work in the show by PETA, it was overshadowed by the uproar concerning a painting by fellow YBA Chris Ofili. Mayor Giuliani attempted to ban the painting and eventually to shut down the show entirely, but ultimately the only effect of his protests was an extraordinary amount of publicity for the Brooklyn Museum of Art and the show went on as planned.

In the same year, Damien's art-installation-turned-restaurant, Pharmacy, which he had set up with PR legend Matthew Freud, became simply an installation for an exhibition at the Tate Gallery. This was followed very shortly by the sale of the restaurant to The Montana Group after plans fell through to expand the fine dining venue into a chain of smaller fast food joints.

The Pharmacy restaurant is just a glimpse of Damien's interest in art beyond the conventional media. His work encompasses all media - paintings, sculptures, video, and everything in between. And he has a steadily growing interest in pop music. He has designed cover art for albums by the Eurythmics, and in 1995 he directed a music video for the Blur song "Country House." He was part of an art and film exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1996, where he showcased his first short film called "Hanging Around". The film featured music by several of his pop star friends from London.

In 1998, Damien himself became involved in a pop group, Fat Les, who recorded two singles that year, appeared at Glastonbury (but didn't perform), and who were accepted to participate in the Music Industry Soccer Six of 1999. There were plans for a Fat Les feature film in 2000, with their first full-length album as the soundtrack, but due to the tremendous flop of their World Cup single, those plans fell through. Damien co-owned the record label, Turtleneck, with actor and friend Keith Allen.

Since even before the inception of Fat Les, Damien has worked on several "side projects" with Keith Allen. In 2002 alone, Damien designed the sets for Glastonbury, a play about the Glastonbury music festival, and designed and directed Breath, the 30-45 second film version of Samuel Beckett's 1969 short. Keith Allen stars in both.

Damien's work has been exhibited widely, in Britain, Korea, the USA, Australia, and countries all over Europe. His work is included in many private collections (most are owned by Charles Saatchi), and in quite a few permanent collections at public museums and galleries. He is represented by London's White Cube, and shows regularly there. He now lives in Devon with his sons Connor (b.1995) and Cassius (b.2000) and girlfriend Maia Norman. He works at his home and in London.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)